When you are creating the truly new, you need to find a way to be relevant. Space, once the government’s exclusive domain, poses the most exciting economic, scientific, and humanistic opportunities for the private sector today.

The proof is all around us. Entrepreneurs are planning:

- Constellations of satellites that promise a wealth of benefits for agriculture, education, disaster prevention, security, logistics, and commerce.

- Dramatically improved internet service, thanks to all those satellites.

- Mining of asteroids and other heavenly bodies.

- Construction of settlements on the moon—and beyond.

- Adventure tours.

- Human exploration of deep space. Destination: Mars.

Meanwhile, rockets are becoming reusable, reducing both the cost of launching satellites, and sending experiments into orbits. And those satellites, once the size of school buses, are now small enough to hold in your hand.

As a result of all this, not surprisingly, established consumer companies with no discernible connection to space are leveraging space themes to inject energy into their brands. And by all accounts, the U.S. government is eager for private entrepreneurs to do their thing, whether as a partner with the government or as a pioneer on their own.

The Challenge

Given everything that we just talked about, it is odd that most Americans are disconnected from space, both the fact of it today and the enormous opportunity of tomorrow. This mirrors the high-tech awareness gap of the early 1970s when consumers wondered why they would possibly ever want a computer in their homes.

The new-awareness gap is a vacuum that the most prominent space entrepreneurs—people like SpaceX’s Elon Musk, Virgin Galactic’s Sir Richard Branson, and Blue Origin’s Jeff Bezos—are rushing to fill. They are thought leaders and storytellers.

Companies that want to thrive in their efforts to secure capital, develop technologies, and make sales would be wise to become powerful storytellers and thought leaders themselves in order to become relevant. They need to connect to a broader audience.

Research and Insights

The first step toward thought leadership is knowing what Americans are thinking. To get an understanding, we conducted a survey. We asked more than 600 representative Americans across the country their thoughts on space today. We learned that they:

- See national security as the top space priority.

- Support private sector activity in space.

- Yet, they want some degree of government regulation, especially when it comes to privacy protection.

- Expect space development to benefit Earth directly.

- Think the U.S. is a leader, if not the leader, in space technology.

National Security

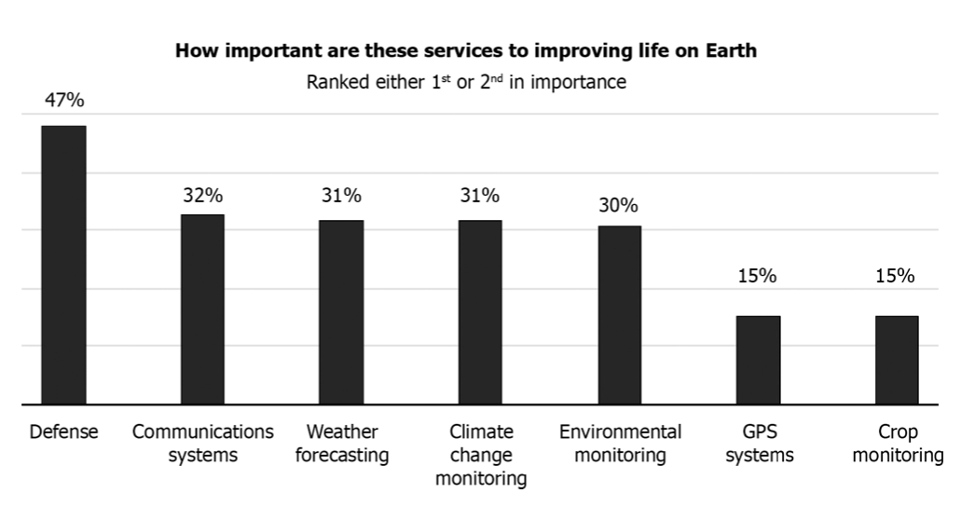

Although space-based systems promise to improve life on Earth in a variety of ways, none was more important to survey respondents than defense, the clear priority among the seven services mentioned.

These findings suggest that respondents may not recognize the important role that space already plays in everyday services like GPS navigation systems (in other words, a failure to get through the rational filter). GPS systems received only 15 percent of the first and second choices, even though most consumers use them in their cars or mobile devices to get them where they need to go.

To us, this data suggests that consumers have a dated mindset—a residual impression that the space industry is primarily government- funded and intelligence-oriented—a “James Bond,” Cold War view if you will.

The Role of the Private Sector

While space has historically been a government activity, Americans today prefer private over government investment in space-based activities, according to our survey. In fact, a majority of Americans actually support private space companies receiving government incentives.

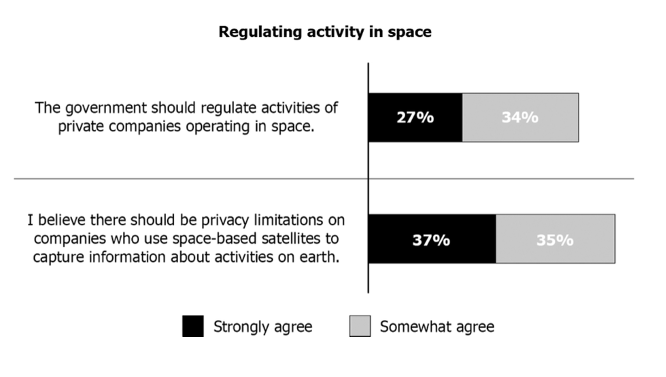

However, the support we have been talking about may come with a catch. Americans are wary of the privacy implications of flocks of satellites capturing increasingly detailed data about activities on Earth.

Strong majorities (72%) believe there should be privacy limitations on satellite companies capturing this data, and many (61%) believe that the government should have a regulatory role regarding private companies engaged in space enterprises.

Earthly Benefits

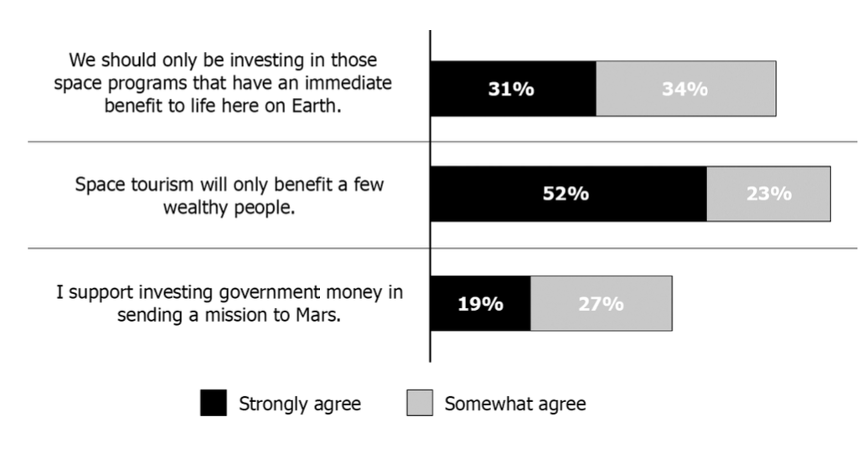

Citizen support for new business activity in space may be contingent on seeing real, practical, and immediate benefits on the ground. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of Americans believe that government investments should be in those space programs that have immediate benefits to life on Earth.

On a related note, space tourism needs to make the case that it will benefit the majority of the population. Three-quarters of Americans think space travel will benefit only a few wealthy people.

Support is also tepid for government investment in deep space exploration. Less than a majority (46%) of Americans support spending government money to send a mission to Mars.

Global Leadership

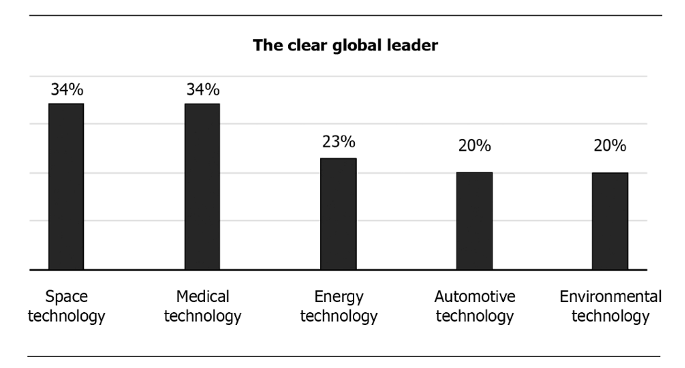

Finally, many Americans believe that the U.S. is a leader in space technology, with over one-third saying we are “the clear global leader.” The finding represents a nice tailwind for new entrepreneurs.

Fewer respondents consider us the clear leader in energy, automotive, or environmental technology.

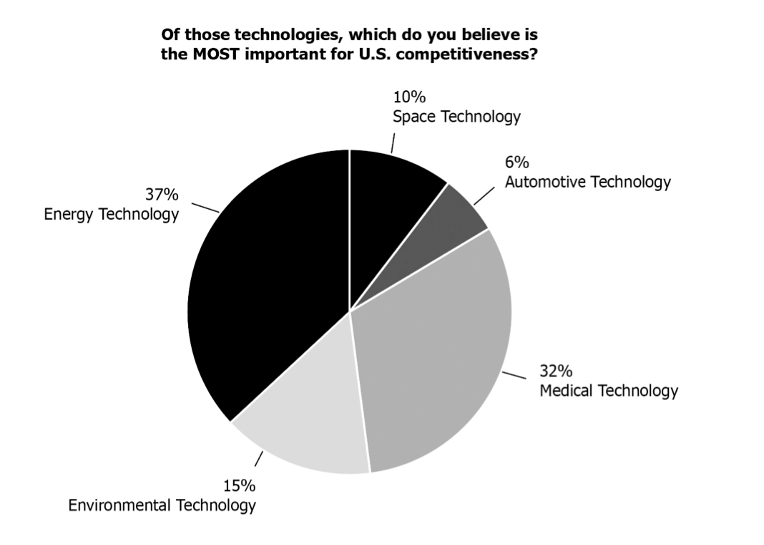

But here is something important to note: Although we are perceived as a leader, Americans don’t see space as terribly important to the country’s competitiveness. Most people place medical technology, energy technology, and environmental technology far ahead of it.

So, although Americans believe we are leaders, they don’t yet view space technology as critical to our national clout. Nonetheless, there is a majority of support for the private sector in space-based activities and an openness to the government providing incentives for private companies. However, Americans will want the government to regulate space activities, particularly when it comes to privacy.

Ultimately, support for business in space may be contingent on the ability to show direct and immediate benefits to life here on Earth. The new data provided by our research reveals a tricky communications challenge for the entrepreneurial space industry.

Dealing with the Challenge

Who is conquering this communication challenge today? Bezos, Branson, and Musk—not because they are great businessmen, but because they’re great communicators. They have fashioned compelling stories about space exploration, tourism, and development that investors, the media, and the public are eager to hear.

They get heard today, but the industry noise is about to get louder. There will soon be thousands of companies in the new space economy, potentially drowning out one another. And as with the computer industry of the 1980s, the industry will shake out to produce winners, losers, and consolidations. As the space celebrities have shown us, success, including capital and customers, requires not only good technology but good stories well-told.

Key Takeaways

The battle for the minds of prospects, the media, and the public entails three stages of communication:

- Americans today simply aren’t yet tuned into space, so unless you’re already a famous entrepreneur, you will need to introduce yourself and your company to the public.

- Once audiences have heard of your company, they are ready to hear the value you offer the world. Preach benefits, not features. For example, you provide real-time pictures of the Earth’s surface for a variety of audiences who need them. You don’t launch constellations of satellites.

- Behavior change. Once your key audiences know you, you need to become relevant to them. You need to ensure their perception is positive and convince them to invest in you, cover you, support you, or buy your service.

It can happen, but the industry has a lot of educating to do.

Space presents an enormous opportunity to improve human lives, expand horizons (literally), and invigorate economies. Great companies with new technologies promise to drive this process, but they need to tell their stories well. Those who do, and who become relevant to their audiences, will thrive as the industry soars—and shakes out.

Those who don’t become relevant will be left wondering why a great technology wasn’t enough.